A Patient’s Perspective: Life with Pulmonary Hypertension

- Category: Living Well, Heart & Vascular

- Posted On:

Author: Millie Ball, UMCNO Pulmonary Hypertension Patient

We all have our stories.

But one thing is true of most of us: We hadn’t heard of pulmonary hypertension until a doctor told us we had it.

Over-simplified, PH is high blood pressure that affects the arteries in your lungs.

It affects the heart, and it is progressive — and it is terrifying when you look it up online. Singer Natalie Cole died of PH.

My advice to new patients: Stop looking it up online.

What is Pulmonary Hypertension?

Pulmonary Hypertension (PH) is different from regular hypertension. PH is high blood pressure in the lungs. It can affect both genders and all ages and ethnicities. Symptoms include shortness of breath and swelling of the feet. Undiagnosed and untreated, it can rapidly lead to death but fortunately, specialized treatment is available. The Comprehensive Pulmonary Hypertension Center (CPHC) at UMCNO is one of a handful of centers in the south that are certified by the Pulmonary Hypertension Association to provide state-of-the-art diagnosis and treatment by nationally recognized PH experts.

Babies can be born with PH. Generally, there are five types, caused by health issues ranging from blood clots to lupus to drug use to heart disease (congenital or otherwise), sleep apnea, to who knows what.

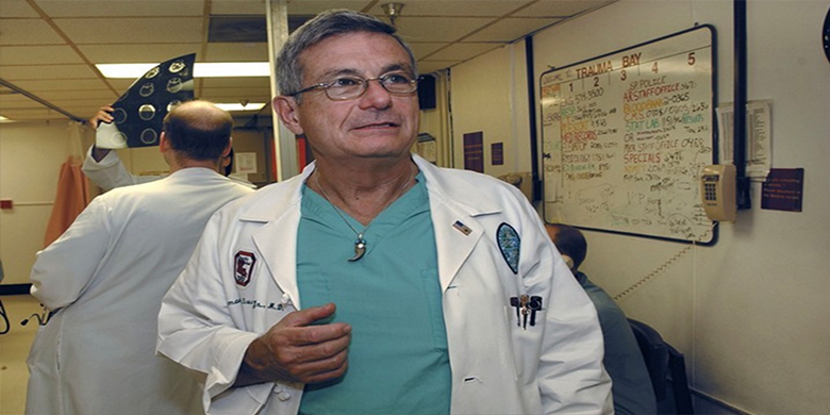

Dr. Bennett deBoisblanc, who’s Professor of Medicine and Physiology at LSU Health New Orleans and one of the PH physicians in the Comprehensive Pulmonary Hypertension Center (CPHC) at University Medical Center New Orleans (and has a bunch of other titles), jokes that some patients are said to have idiopathic PH, “because we are the idiots and don’t know its cause.”

Everyone calls him Dr. Ben because most stumble over the French name of this native New Orleanian…Bwa-blon is semi-close. An avid daily runner, he’s a nationally respected researcher in PH, who has won awards for the way he relates to patients, and for his work in Charity Hospital’s Intensive Care Unit during Hurricane Katrina. He makes patients laugh, gives us his cell number, and makes us feel — despite what we might have read — that everything will be all right.

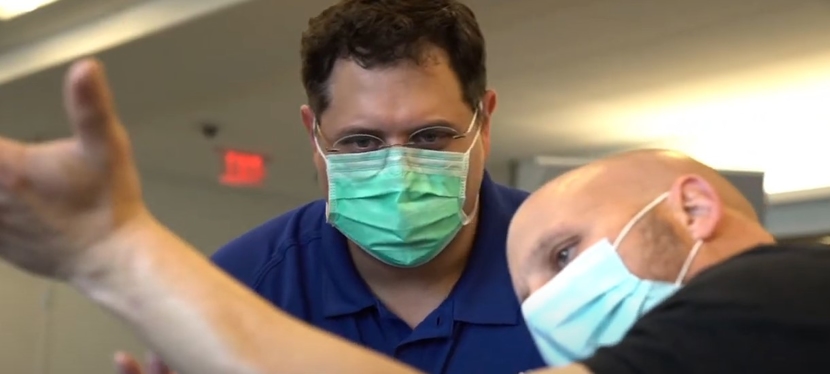

As do his LSU colleagues who I have seen as well at the UMCNO Comprehensive Pulmonary Hypertension Center: LSU Associate Professor of Medicine, Dr. Matthew Lammi (he also gives his cell number), Pulmonary/Critical Care Fellow Dr. Sneha Samant, and CPHC Nurse Coordinator, Monique Brown, a master organizer, who makes PH patients feel like they are her friends. Tulane School of Medicine physicians, including Dr. Lesley Saketkoo and Dr. Shigeki Saito, also are a core part of the CPHC.

So how do you end up with this exceptional team?

Shortness of breath is a typical first symptom, as are fatigue, heart palpitations, dizziness, swollen ankles — in other words, the same symptoms as too many other illnesses. Some patients go several years undiagnosed before finding a specialist who has worked with PH patients.

My first symptoms showed up three years ago when I thought I had been hit with 24-hour flu during a Thanksgiving visit to a mountain town in North Carolina, 4,118 feet above sea level. I had spent vacations there for years, with no problems.

My second night there, I threw up, my heart raced, I was nauseated, and didn’t feel like eating. It lasted 24 hours.

I returned to the mountains over New Year’s, and it happened again, also on my second night.

In the spring, my husband and I flew to Denver, the mile-high city, 5,280 feet above sea level. I felt woozy in the airport and came down with similar issues by early evening. The next day, we drove up to Minturn, CO, 7,861 feet. I went to bed for three days, vomited, my mind confused. “I need to go to Urgent Care,” I finally murmured.

A nurse put a pulse oximeter on my index finger to measure the oxygen level in my blood. It was 61. “Is that bad?” I asked. She shared a glance with another nurse. Healthy people usually have 95-99 percent oxygen, but anything over 90 is OK.

High altitude is not my friend.

The first thing I did was buy a pulse oximeter at a drugstore. Then I called a pulmonologist, who ordered a pile of tests, and walked me up and down his office hallway, shaking his head, and saying he was surprised I could be so chatty when most people with my blood oxygen numbers could barely breathe.

I was diagnosed with sleep apnea, a disorder in which you stop and start breathing repeatedly while you sleep. Untreated, it can cause heart damage, and increase the risk of Alzheimer’s, say some researchers. My tester told me that I was one of four patients in eight years whose oxygen level dropped into the 60s when I slept.

The pulmonologist ordered a continuous flow oxygen concentrator, which sucks oxygen out of the air and pumps it into a tube linked to a CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure)mask when I sleep. It’s not pretty.

I passed the other breathing and heart tests. But at our final meeting, the doctor said, “You either need to see Dr. Bennett deBoisblanc at LSU or go to the Mayo Clinic.” I cried.

I saw Dr. Lammi and Dr. Ben, and underwent a heart catheterization, the gold standard test for PH at University Medical Center in August 2015. I was told that I have PH, but a mild case. Blood pressure meds were prescribed. And Dr. Ben said I should weigh 130; I told him I was born weighing more than that, but I’m trying.

Linda Gates, who has had PH for 15 years, heads a support group that I now attend. Another woman, from Houma, who has had PH for more than 17 years leads a support group there. When they were diagnosed, there was no treatment for PH. It was almost a death sentence. Now there are more than 15 medications. Some types of PH respond better than others.

Linda had just returned from Iceland when I met her, which was encouraging. Travel is my passion, and my job was writing about travel.

Unfortunately, the Medicare-mandated company that was supposed to supply my medical equipment sent me big clunky oxygen tanks that you can’t take on an airplane. I was told, quietly, by an employee, that my chances of getting a small portable oxygen concentrator were slim. You have to have an FAA-compliant oxygen concentrator to fly in commercial airplanes, where pressurization is the equivalent of being 6,000 to 8,000 feet above sea level.

Fortunately, I was able to pay for one, $2,500 for an Inogen One 3 G that weighs five pounds and totes like a crossover purse when I exercise or fly. That’s me, wearing my oxygen concentrator and walking my 11-pound, white Havanse pup many mornings in Audubon Park.

To fly, each airline requires its own letter of permission from a doctor. “Hello, Monique, I need Dr. Ben to sign another letter!”

As I write this I’m on yet another trip — three airline letters required: United, American, and Etihad Airlines from Abu Dhabi. There’s our regular luggage, plus my portable oxygen concentrator, my constant flow oxygen concentrator, my CPAP, and my dear husband, Keith, who helps lug it all around with me. We’re doing our bucket list destinations: a while back tulips in Holland and this month ruins in Petra, Jordan.

Thank you, Dr. Ben, Dr. Lammi, Dr. Samant, Monique, Linda Gates. I don’t know where I’d be if I hadn’t found you all at University Medical Center.

For more information on PH and the CPHC at UMCNO go to www.umcno.org/cphc.